The Battle for Science in the Age of Misinformation

In “Distrust – Big Data, Data Torturing, and the Assault on Science,” Gary Smith discusses the ills plaguing science and the public’s trust in it. The central theme is that science and scientific credibility are under attack on three fronts: internet disinformation, p-hacking, and HARKing (Hypothesizing After the Results are Known). These threats work together to compromise the reliability of scientific studies and to exacerbate the dwindling trust in its findings.

The internet has long been a double-edged sword; while it provides a platform for free expression and the collection of human knowledge, it’s also a petri dish for disinformation. Smith describes how falsehoods proliferate online, often accelerated by algorithms designed to prioritize engagement over accuracy. This phenomenon is particularly dangerous when tackling real-world challenges like COVID-19. Disinformation has led to widespread skepticism about science-backed interventions like vaccines. In this age of “fake news,” public trust in mass media has also taken a hit.

Real Science, Real Results

Gary Smith lauds the success of mRNA vaccines—a stellar example of science working as it should. With a 95% drop in infections reported in randomized trials, the vaccines developed by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna have proven to be nothing short of miraculous. Smith points out that these vaccines’ effectiveness is supported by solid data, contrasting the unsubstantiated claims made about hydroxychloroquine and ivermectin. This distinction between evidence-based medicine and wishful thinking underlines the importance of critical thinking and analytical rigor.

AI: A Story of Broken Promises

As usual, Smith brings a dose of reality to the overly optimistic world of artificial intelligence. After IBM’s Watson stole the spotlight by winning Jeopardy!, it was hailed as a future game-changer in healthcare diagnostics. However, the reality has been far less revolutionary. Smith dissects this failure, highlighting the critical weaknesses of AI. AI is not the impending super-intelligence it is often promoted to be, which is critical to understand as we navigate the ever-evolving landscape of AI technology.

[Side note: Gary and I have good-natured debates about the importance of ChatGPT. He argues that chatbots are “B.S. Generators” and that’s actually a fairly apt characterization. I used to work with a software developer who admitted that when he didn’t know the answer to a question the project manager was asking him, he would “blast him with bullshit, just BLAST him!” and by that, he meant that he’d just overwhelm him with technical-sounding jargon until he went away confused. Assuming that he wasn’t just choosing words at random, the technical jargon he blasted the manager with was probably something he’d heard or read somewhere. Sounds a bit like ChatGPT, doesn’t it?

However, there’s a difference. ChatGPT is using our prompts to find the most appropriate (and surprisingly grammatically correct) response. As Smith points out, chatbots don’t know what words mean or what the world is like, they’re just finding patterns in their training data and parroting back to us what people usually say. However, it’s not just nonsense; you could say that it’s giving us glimpses of the sum of human knowledge available as of 2021! Of course, information can be wrong on the internet, but ChatGPT is basically a linguistic interface that boils the entire web down to the essence of what you’re probably looking for. Contrast this with Google’s endless list of possibly helpful links or Wikipedia’s firehose of overly technical information… have fun trying to extract the answer for yourself! I think ChatGPT is revolutionary. It’s not actually intelligent, but it will save us countless hours and teach us things in the most efficient way possible: through question and answer sessions.

Regarding the downside of chatbot “hallucinations”, guess what: you should always be skeptical of what you read. If you Google the age of the universe right now, it gives you the speculations of a recent paper instead of the scientific consensus. Sometimes, when it’s important, you need to verify information. Chatbots are no better or worse than what people have said about your topic of interest on the internet. Most of the time, the “wisdom of the crowds” is fine. And it’s still up to you to figure out when it’s not.]

Smith often says that the danger is not that AI will get smarter than us, but that people will think AI is smarter than us and rely on it for things they shouldn’t. Smith uses the entertaining BABEL automatic essay generator as a cautionary tale about relying on algorithms. BABEL basically cranks out random nonsense, but uses a lot of big words, and gets scored highly by automated essay graders (yes, automated graders can be “blasted with B.S.”). It’s an amusing yet stark reminder that while technology has come a long way, it can still be gamed or manipulated. Smith uses this example to show the pitfall of over-reliance on AI for tasks that require nuanced understanding, an essential lesson for educators, data scientists, and policymakers alike.

The Disturbing Trend of Retracted Studies

Smith doesn’t shy away from criticizing the scientific community itself, particularly the increasing rate of retracted papers. The integrity of the scientific process needs an upgrade. Retractions can shake public trust and, as Smith notes, signal a deeper issue with ‘p-hacking’ and ‘HARKing.’ These practices distort data and hypotheses to manufacture significance, undermining the credibility of entire fields of research. Smith exposes the incentives that lead to shoddy peer reviews and phony journals.

The concluding chapter, “Restoring the Luster of Science,” is a manifesto for renewing public trust in science. Smith exposes the downsides of “filter bubbles,” where algorithms shape our realities by reinforcing existing beliefs and biases. He also wrestles with the ethical implications of regulating speech to combat disinformation without infringing on civil liberties. This chapter serves as a summary of the book’s overarching themes and offers a pragmatic way forward for educators and policymakers.

I was particularly happy to see his last three recommended actions to help restore the luster of science:

-

-

- Courses in statistical literacy and reasoning should be an integral part of school curricula and made available online, too.

- Statistics courses in all disciplines should include substantial discussion of Bayesian methods.

- Statistics courses in all disciplines should include substantial discussion of p-hacking and HARKing.

-

I couldn’t agree more and in fact am currently working with Julia Koschinsky at the University of Chicago on designing a course that takes up the challenge: “Becoming a Data Scientist in the Age of AI – Developing Critical Skills Beyond Chatbots”.

Missed Opportunities

The book does leave a couple stones unturned. Smith understandably avoided the more thorny issues surrounding social media’s premature suppression of the COVID “lab leak” hypothesis (it got muddled up with the “intentional bioweapon” conspiracy theory) which could have added a nuanced layer to the discussion about regulating misinformation for public safety. The topic has been the subject of significant controversy and debate, particularly because it touches on complex issues involving science and politics. (Btw, the most entertaining defense of the hypothesis was undoubtedly this one by Jon Stewart).

The challenges that tech companies face with real-time content moderation, especially when dealing with rapidly evolving scientific matters where the truth is not easily discernable, are significant. There are ethical dilemmas related to freedom of speech versus public safety, debates about the responsibility of tech companies in moderating content, and questions about how we navigate “the truth” in an age overwhelmed by information and misinformation alike. There are no easy answers here, but it would be interesting to read how a thinker like Smith would navigate these murky waters.

I also think the book missed a golden educational moment concerning reported vaccine efficacy…

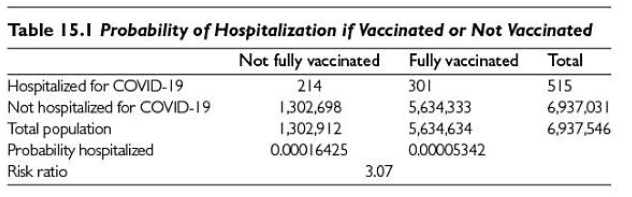

Look closely at Smith’s tables below…

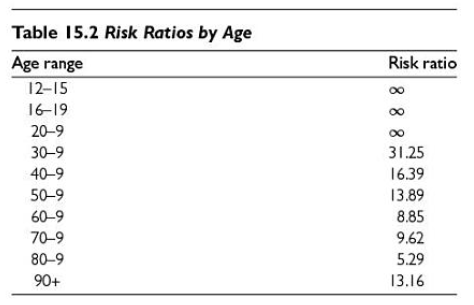

You may wonder how an overall odds risk ratio can be 3.07 when none of the risk ratios are that low when grouped by age!

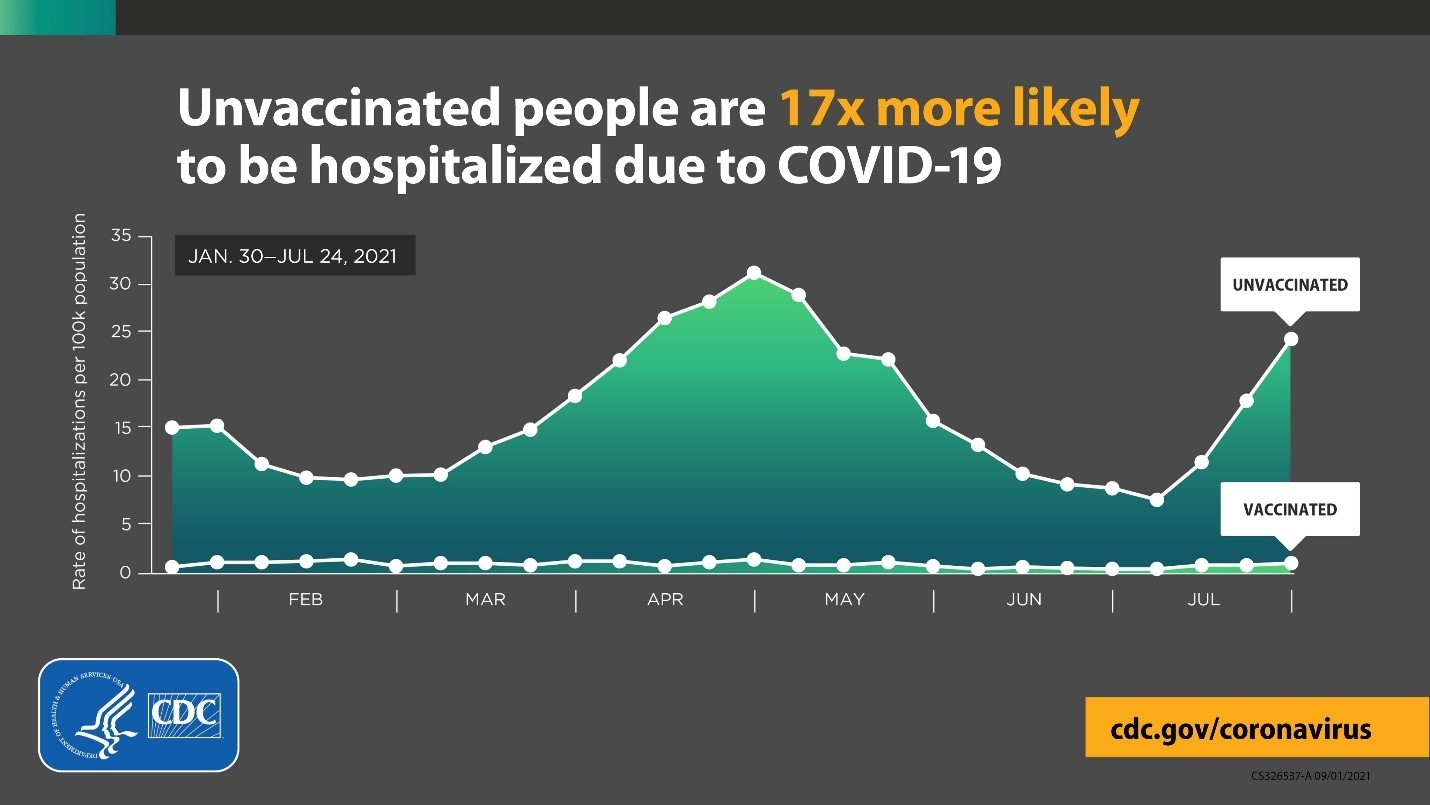

Smith would instantly know the answer, but most of us wouldn’t. The majority of comparisons we see between vaccinated and unvaccinated look more like his first chart, with a 2-4x benefit of vaccination…

It’s a straight-forward comparison of the probability of hospitalization for vaccinated and unvaccinated people? What could be wrong with that?

It turns out that it’s very misleading to directly compare vaccinated people vs. unvaccinated people, because it’s not an apples to apples comparison! I’ll take a wild guess and say that the population of vaccinated people are more concerned about catching COVID-19. Specifically, they are more likely to be elderly, overweight, or have pre-existing conditions. That means that these simple comparisons between the two groups are greatly understating the benefit of vaccination! The reality (when controlling for age, as in Smith’s second chart) is more like this…

The CDC did their best to control for all of the variables, but even their analysis is probably understating the benefit, given the 19x improvement shown in the randomized controlled trials.

Conclusion

Gary Smith’s “Distrust – Big Data, Data Torturing, and the Assault on Science” is a timely, critical examination of the various threats to scientific integrity and public trust. It serves as both a warning and a guide, tackling complicated issues with nuance and depth. For anyone interested in science, data science, education, or public policy, this book is an invaluable resource for understanding the modern landscape of disinformation, scientific misdeeds, and the quest for truth.