The first time I suspected my daughter was a mutant was when she was 8 years old and said something about being excited to be the age of her favorite color teal. I had heard about synesthesia, which is a rare hereditary perceptual condition in which senses are combined in surprising ways: sounds may trigger physical sensations, music may be associated with colors, or letters and numbers can have particular colors “projected” onto them. I showed the wiki page to my wife and told her that I thought our daughter was a “synesthete” and she was rightly skeptical. We saw in the article that most synesthetes think that A is red, so I shouted out to my daughter in the other room: “What color is A?” and Jacqueline shouted back “Red!”

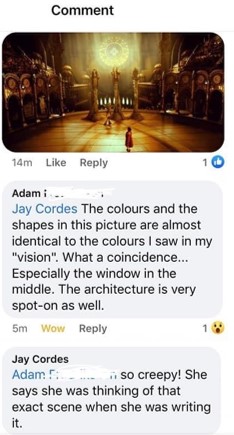

An online test that asks you to pick the precise color for letters and numbers in random order three times and measures the consistency of your answers. She took it and passed with flying colors…

Jacqueline’s color consistency across three trials

Evidently, she’d had it her entire life, because she remembered blue and green being important parts of turning two and three as well.

Synesthesia and Memory

The first sign that this strange color phenomenon could be a superpower was when Jacqueline won the pi memorization contest in 5th grade. It wasn’t so much how many digits she memorized that seemed unusual (80 digits), but the speed with which she memorized them. She came to class with only 40 digits memorized, but when a competitive boy pried that info from her and then told her he’d beat her by ten digits, she quickly doubled her number of memorized digits and ended up winning the contest in a landslide.

Studies have suggested that synesthetes tend to have enhanced memory and Jacqueline’s history seems to support that. For kicks she memorized the titles of all 100 tracks on Radiohead’s 9 studio albums, forwards and backwards (more on Radiohead later). Probably most unusual is her quick memorization of piano pieces (her teacher doesn’t know how often she’s memorized new pieces the day, or even the hour, before her lesson, shhh!) BTW, synesthetes also tend to be creative people, and that’s true of her as well (she created all of the synesthesia-related visualizations below).

Mutant superpowers evidently can also lead to laughs, such as the time she went to school dressed up like the Terminator for Halloween (the Summer Glau version from the Sarah Connor Chronicles TV show). A kid challenged her, saying “If you’re the Terminator, then what’s pi?” She said that when she quickly recited the 80 digits from years ago, he literally jumped back in shock.

Synesthesia and the Brain

So, why would I think you care about any of this? Well, it turns out that synesthesia provides a unique window into how the brain works. From just a few observations about Jacqueline’s colorful world, we can deduce surprising things and even a few that would be practically impossible to know otherwise.

Bishops have color (sometimes)

Jacqueline started learning chess a year ago, and the pieces soon gained projective color: Kings are yellow-orange, Queens are primrose, Rooks are dark green, Bishops are yellow, Knights are light brown, and pawns are light red. That’s interesting in itself, but isn’t the most surprising.

What’s surprising is that when I showed her a bishop with the slit of the hat hidden in the back, she said it lost its color. As you rotate it, she sees it turn bright yellow, and then a slightly dimmer yellow when the slit is in the front (when it looks like Elmo with his chin up).

This one simple experiment tells us many interesting things:

-

- An independent subconscious mind exists. Obviously Jacqueline knew it was a bishop, whether or not I turned it, but her subconscious mind was categorizing it based only on the slit and would “change its mind.”

- The subconscious isn’t really any better at classifying images than regular modern machine learning approaches. In A.I. research, a constant source of frustration is how brittle neural nets are in classifying images. One seemingly trivial change in a picture can cause machines to no longer recognize something that’s obvious to human beings. It turns out that the human brain has the same problem! Hiding a small feature (the slit in the bishop’s hat from the “training data” from chess.com) led the subconscious to no longer recognize the bishop, even with all of the other similarities between the chess pieces. The only reason we’re better at classifying images than computers is because our conscious mind has the ability to overrule the subconscious and use reasoning like “rotating an object doesn’t change it” to continue to recognize objects even when our hard-wired image recognition fails.

- Our brains don’t use either/or categorization. The fact that the bishop had different shades of yellow depending on how closely it resembled the digital bishop Jacqueline was familiar with shows that the mind categorizes it as “more bishop/less bishop” rather than “bishop/not a bishop”. This is also similar to how neural nets work.

Synesthetic colors can develop and change over time and could give clues about the purpose behind the phenomenon. Jacqueline participated in several studies over the years and was surprised by the fact that a recent study showed that she chose different colors for a few letters than she did when she was 8. She says that she can still think of those letters as their old colors (unlike most other letters, which she can’t imagine being any other color), but they’re kind of a strange mix of the two colors.

For example, C is a mix of yellow (the color she chose as an 8-year-old) and a light gray-blue (the color she prefers now). It’s not green, but an impossible combination of blue and yellow. If you look at the image below with crossed eyes so that the C’s combine into one image, you’re seeing it pretty close to how she sees it.

Jacqueline came to realize that letters with these impossible colors are actually transitioning from an old color to a new color, and she suspects that almost all of them are due to the piano keyboard. When she started playing piano at age 7, the piano keys themselves gained the projective color of the letter they’re named after (see the keyboard below and notice that A’s are red).

Here’s the kicker: the original colors for A through G weren’t all distinct, but the colors that they’re evolving towards are. So, it’s possible that the synesthetic mind has the goal of giving objects distinct colors (easier to distinguish means easier to remember?) and is willing to “change its mind” in order to make that happen.

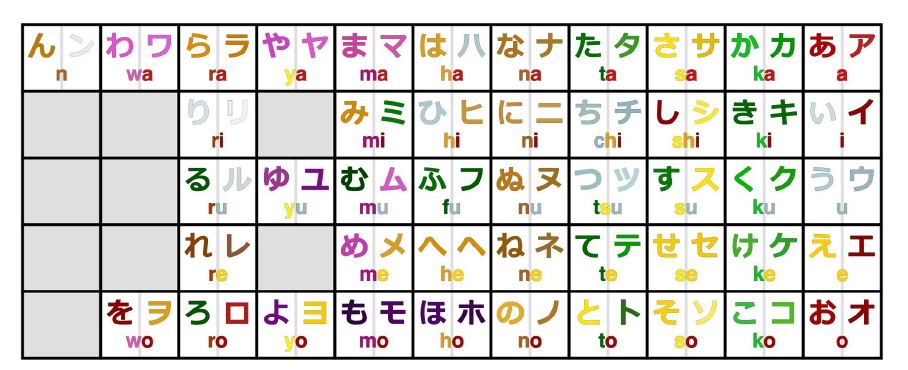

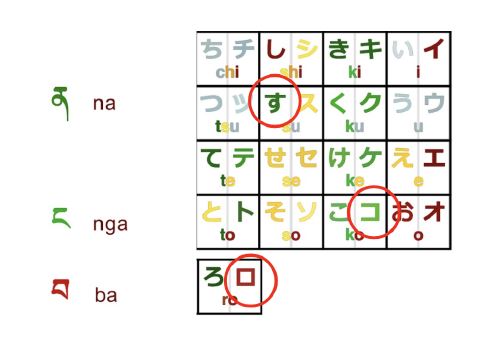

The only letter that’s transitioning from one color to another that can’t be explained by the piano keys in the letter “n”. Jacqueline suspects this is due to her learning of Japanese and her brains attempt to establish consistent color categories for the hiragana alphabet…

Jacqueline’s Japanese Hiragana Colors

Her synesthesia is struggling to establish consistent colors for each of these columns because the shape of characters is evidently the primary driver of color.

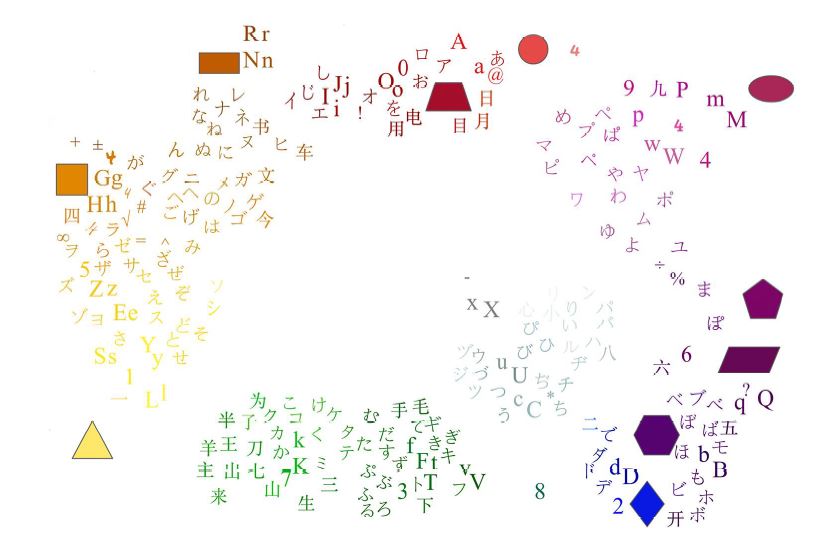

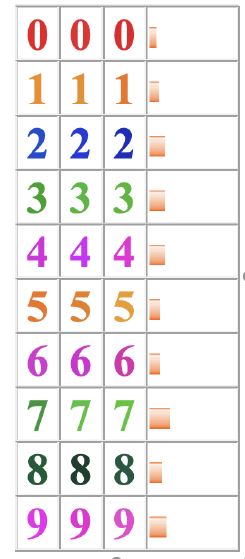

Here’s kind of an overall map of her colors for a variety of shapes and characters where it’s easier to see the similarities in each group…

All the Colors

But I digress.

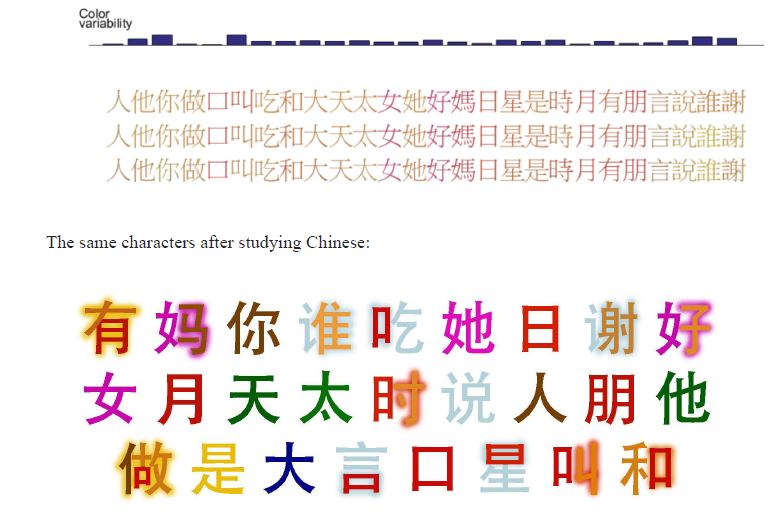

It evidently takes much longer (years) to change colors than to establish them in the first place. Jacqueline didn’t notice how long it took for the piano keys to gain color, but she did see notice how fast Chinese characters gained color, because she participated in a synesthesia study when she was in 8th grade that tested her on her color response to Chinese characters before she had taken any Chinese. While taking Chinese in 9th grade, the characters dramatically changed in a matter of weeks…

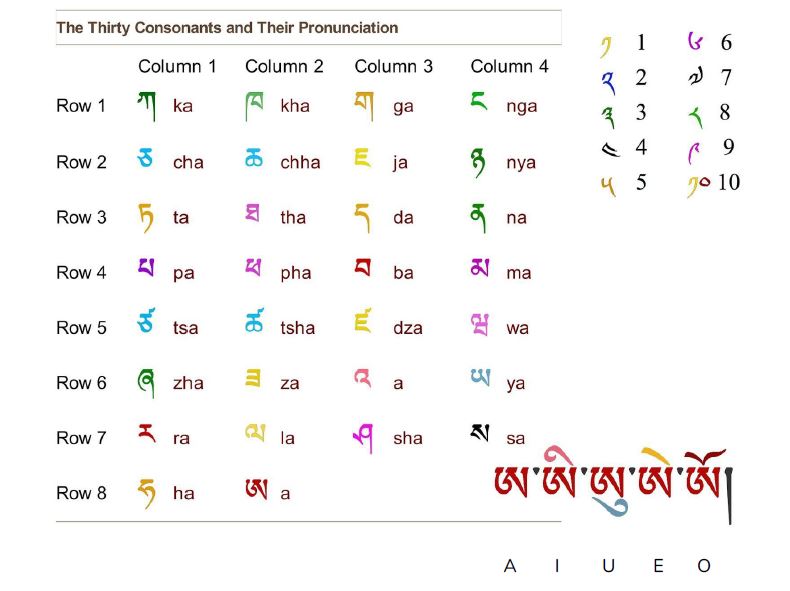

With this in mind, Jacqueline inadvertently played a prank on her synesthetic mind by learning the Tibetan alphabet for a school project. She had teammates attempting to predict the future colors based on the information above, and they got most of the predictions correct based only on the shapes and sounds of the Tibetan characters. She was careful not to look at their predictions before studying the characters and establishing their colors…

It’s sometimes easy to find similar-looking characters from her past languages that determined the color for the new Tibetan characters…

So what’s the prank? Look at the numbers in the “Tibetan Colors” image above. Notice that the Tibetan character for five looks like a 4 and the character for eight somewhat resembles a 7. Based on her “All the Colors” map, Jacqueline’s synesthetic mind instantly assigned those numbers the wrong colors! The other numbers had no color until she learned them well enough to instantly recognize them and they got the appropriate color based on their meaning. The problem is that when she learned the character that means seven, it should get the color of 7. But her mind had already assigned that color to the character for eight, which just happens to look like a 7! So how does her mind resolve that difficulty and still maintain distinct colors for each number (we know that’s important from the piano keys)?

That’s right, the character for seven gets no color! Who knew you could play jokes on your subconscious mind by learning Tibetan? (There’s a sentence that’s never been written in the history of the world)

Weren’t we going to talk about Radiohead?

Oh yeah, so in addition to all of this weird character to color stuff, Jacqueline discovered in high school that she also has musical chromesthesia, which assigns colors to particular sections of songs. She first noticed it when playing Rachmaninoff on the piano because of the dramatic shift in color that takes place during the piece.

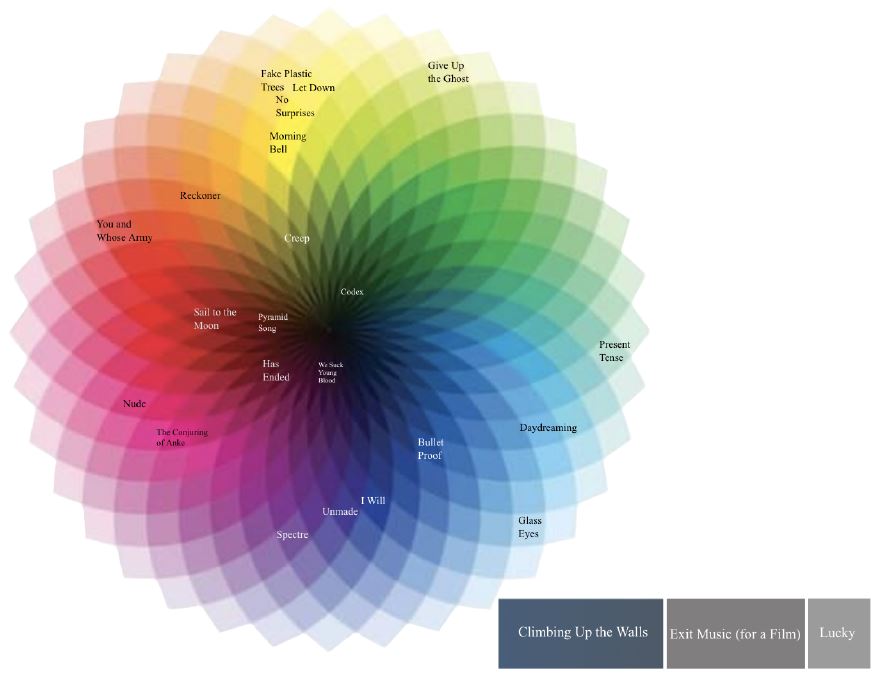

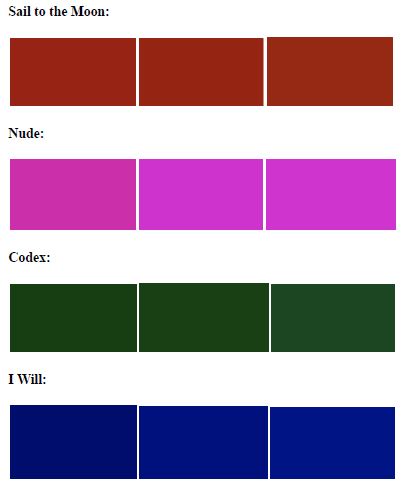

Then, one day, a song I snuck into a playlist on her phone stopped her in her tracks at school: “I Will” by Radiohead. It was a vivid blue through the whole thing! I had hoped she would appreciate the incredibly talented band, but had no idea that her fandom would quickly surpass my own as she discovered that they had many songs that had vivid and consistent colors throughout!

Jacqueline’s Colors of the Radiohead Songs

Consistent colors on a color-picker between repeated trials

Consistent colors are rare from other popular artists and in fact, even about half of the covers on YouTube of these exact songs lose the color for a variety of reasons. Jacqueline also experimented with different tempos and found that practically all of Radiohead’s pieces lose color at precisely 1/2 speed or double speed. Only one piece seemed to be “too fast” in the sense that it’s range of colors was 50-100% speed instead of the usual 75-150%. It’s as if the music were fine-tuned by a synesthete with color, literally, in mind.

Spookily, it looks like this may in fact be true: Thom Yorke, the primary songwriter for Radiohead wrote the following in the foreword to a book on his lighting and stage designer Andi Watson:

I watch a video sometimes, and I just say to him how did you know this tune was that colour?? I guess we are firm believers in synaesthesia…we won’t have even discussed it, but he just seems to know the right colour.

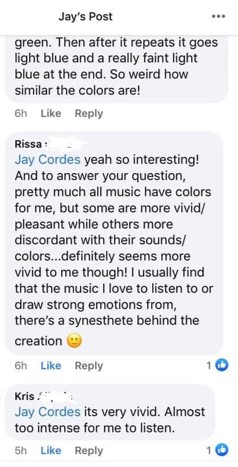

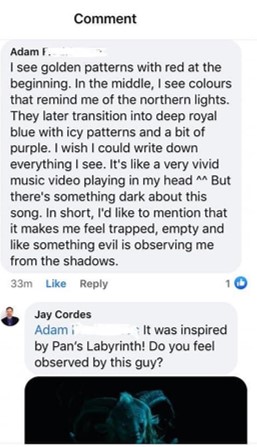

Anecdotally, when Jacqueline runs into other Radiohead superfans, they seem surprisingly likely to have musical chromesthesia. We joke that Radiohead is like the Cerebro machine in the X-Men that Professor X uses to find other mutants.

Then it occurred to us that Jacqueline herself is a composer and it would be interesting if other synesthetes respond to her music. I posted a link to one of her piano pieces Labyrinth on a Facebook page for synesthetes and they definitely seemed to think it was more vivid than typical music…

Spooky Stuff

As long as we’re getting spooky, we may as well go all the way down the rabbit hole. It turns out that Jacqueline has another type of synesthesia that doesn’t even have a name yet and we’ve only found a couple other cases online. Except for a handful of pieces, the music of Bach doesn’t have color for her. However, when she’s memorizing it, it has something else: images. It could be a sailboat, an old man, or even a specific memory of a scene from her grade school. They seem to be completely random and not related to the music.

The images are strangely specific and only pop into mind while she’s trying to play a piece by memory. Then, once she knows the piece well enough to play it by muscle memory, the images go away (but she can recall what they looked like). Not only that, if she then forgets the piece and relearns it, the exact images come back in the same exact sections of music!

Another interesting fact is that while some pieces have color and images, they never occur at the same time. It’s almost as if the mind is using color to remember things, but without that possibility, searches for and retrieves random images to help with the task (“this is the pumpkin chord”).

Anyway, back to spooky stuff. It’s about to get all supernatural up in here, so buckle up. I’m a rational scientist guy, so for the record, I think the following is just a coincidence. Even though it’s not the only time this has happened, I’m sure I’m forgetting about all of the times it didn’t happen, so I think it’s just the availability heuristic that makes it seem like this is a thing. Anyway, this happened…

Anyway, this blog post has probably jumped the shark at this point, but I just wanted to share some of our interesting observations about the mutant who grew up in my house.

In her words, below are all of her types of synesthesia. Anyone experience any of these?

-

-

- Projective grapheme-color

- Projective day-color

- Projective colors for school subjects (plus associative colors for teachers of core subjects–they gain the color of their subject) or any well-known group of items in a list, for example world languages, countries

- Projective colors for keys on the piano

- Projective colors for basic shapes

- Auditory-tactile

- Associative musical chromesthesia (for musical sections instead of chords or notes)

- Associative images for some sections of pieces that I have memorized as I’m playing them

-