I would not describe myself as a “gambler.” Although I enjoy thinking about casino games, I almost never play them. One exception was the time my wife and I went with friends to a casino in Barona. While we were there, we saw a promotion: if we join their card club and play slots for 2 hours, they would refund our losses or double our wins, up to $200. After confirming that we could ensure ourselves no worse than a break-even gambling session, my friend and I hit the video poker machines. We played for $1 a hand until there were 15 minutes left. I still had $150 of my $200 left, so I bumped up the bets to $5 each. Then, I hit a royal flush. I waited at the machine until someone came and counted out $4000 in cash. After he handed over the stack of money and left, I realized that any losses occurring now were actual losses, so I stopped playing and waited out the remainder of the time before collecting my additional $200 matching prize and leaving the casino. I haven’t played video poker there or anywhere else since then. Casinos must hate guys like me.

When I started playing online poker (against people, not casinos), I only invested $50 and slowly built my bankroll up to $100. At that point, I was so paranoid that other players would cheat me or beat me out of all of my money, I took out my initial $50 back out. From then on, I was on “house money” and never looked back.

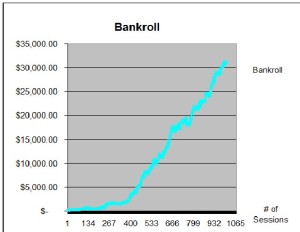

After my father-in-law found out that I was playing online poker and saw my chart above, he took my wife aside and advised her to secretly stash away some money so she could take care of our daughter when I inevitably blew through all of our savings. She just busted up, because he obviously didn’t know me very well.

The first guy that I met with an actual gambling problem was someone I worked with when I was a software developer consulting for HdL Software. He would not only sneak out of his house at night to go to the casino (leaving his young kid alone), his game of choice was the one with arguably the worst odds in the house: Keno. It wasn’t enough that he played with a horrible return on investment; he would have the computer to continually auto-pick his numbers for him without even requiring him to push a button. And as if that weren’t enough, he’d have two machines running at a time and burning through his money while he would stand there enjoying a drink.

Of course, occasionally he’d show up at work with a wad of cash talking about his big win. However, even he had no illusions about the direction of his cash flow. He estimated that his hourly loss was around $100 for each hour he spent in the casino. He wanted to quit, but just couldn’t. I was curious why, if he was going to gamble, he wouldn’t at least play games with much better odds, like blackjack. Eventually, I figured out that it was because blackjack doesn’t have the potential for a “big win”. You typically can only win twice the amount that you bet. So I came up with an idea for him.

I asked him what he considered a “big win” and he said $20,000. I looked it up, and for you to win $20k with a $1 bet, you need to pick and hit 8 numbers. The chances of this occurring are 0.00043%. So here’s what I told him to do: learn and play basic strategy at blackjack, but when he wins a hand, let it ride and bet his winnings on the next hand. For example, if he were at a $1 table, if he doubled up 15 times in a row, it would be worth $32,768! His response was that the chances of winning 15 hands in a row was too incredibly low. I showed him how, at about 49.5% chance of winning, the odds of 15 wins in a row is 0.00262%, or about 6 times as good as the Keno big win, and it paid over 50% more! When the logic sank in, rather than switch to blackjack, he actually stopped gambling for the first time since I’d known him. Until that moment, he had never truly realized how badly the odds were stacked against him. Of course, he started gambling again a few months later, but I had almost cured him.

The second guy with a gambling problem I met was someone who got so tired of losing his money at online poker, he had told the bank to stop allowing him to send money to online casinos. When he found out I had developed a simple all-in or fold poker strategy that was exploiting the fact that some poker sites allowed you to buy-in as a short-stack, he desperately wanted me to teach it to him. I was pretty sure that “the System” would probably work for him, as it had for others who knew much less about poker, but had a feeling it wouldn’t end well. However, the question nagged at me: if someone with a gambling addiction actually had a strategy that made money, would he still have a gambling problem? Or would he just be a profitable work-a-holic?

I eventually shared the System with him and at first, he was a poker monster. He made $12,000 in the first month. Once, when he took my wife and me out to dinner to celebrate his success, I asked him to show me his bankroll chart and it didn’t quite look like mine. His had occasional huge losses in it. I asked what that was about and he said that other players would heckle him through the chat box and challenge him to heads-up matches, which he would eventually accept and get crushed. He turned to my wife and said “I’m sick Cathy.” (she’s a psychotherapist) “It’s horrible when you know it about yourself.” I told him to turn off the chat window!

He seemed to be under control and profitable until he told me about his plans to play at the $50 big blind level. Even buying in as a short-stack meant he’d be betting $500 on each hand. I had never played at or evaluated the system above the $20 big blind level, so I didn’t recommend it. The System was exploitive, not optimal. That means that it could be beaten by knowledgeable players, and generally, the higher the stakes, the more knowledgeable the player. Even though my friend was making a lot of money, he had gotten bored. His first trip to the $50 big blind level didn’t go well; he lost $4500 in one evening. He didn’t keep me up-to-date on his results anymore, but when I ran into him much later, he admitted that he had given the entire $12,000 back to the poker economy. The experiment had run its course and his gambling addiction had emptied his wallet again, even when the game should have had a positive expected return.

Other friends had their own stories with the System. One friend said he was willing to invest $1000 and was full of confidence. I told him to start out at the $2 big blind level, betting $20 per hand, and trained him for about an hour at my house. He had learned the strategy well and was ready to go home and try it on his own. An hour later, he called us up…

“I’m taking you guys to steak dinner, I’m up $1000!”

“That’s not possible at the limits you’re playing at.”

“I’m looking at my balance right now and it says up a grand.”

“Go back to the table you were playing at.”

“Hmm, it’s not letting me buy back in for less than $940.”

“The maximum buy-in for those tables is $200!”

Then, I realized what had happened. He had accidentally played at 10x the stakes he intended to. He had been betting $200 per hand instead of $20 and just happened to get lucky. His ADD sometimes caused him to let little details like that slip by. However, on the bright side, it also gave him the super-power to play 10-12 tables at a time, which would have given me a stroke due to the stress of trying to keep up. He eventually made well over $10k and unlike the gambler, he kept his winnings.

My favorite success story came from a friend who couldn’t be more different from the problem gamblers. He promised to stick to the System and told me “as an upstanding actuary, I have absolutely no creativity.” He told me he didn’t play poker and didn’t like gambling and I told him “you’re perfect.” His statistical mind and distaste for gambling gave him endless patience to play at low stakes. He never went down more than $2.50 and was continually playing at micro-stakes to ensure it stayed that way. I started to harass him into playing higher stakes and eventually his wife joined in, saying “I don’t want my husband playing a video game all day for $4 an hour.” He finally relented to the pressure and bumped up the bet-sizes. It paid off as he soon pocketed a few thousand dollars. At one point he wrote me this email:

“I had a rough night tonight and then a roller coaster ride at the end. Could not win anything. Even my best hands ended up split pot, until my final table.

$4 bb…I get an AK so of course I go all in. I get 1 caller and I get 2 more K’s on the draw to beat his pocket 10’s. Whew. I now have $120 in my stack. Then on my last hand, I get an AK suited. I almost did not want to go all in given my bad luck all night, but I follow the rules and go for it. One guy folds and says ‘it is tiring folding after the stupid ass betting in front of me.’ Then, the next guy calls me, the same one from the last hand.

The cards come out as 7,6,A,A,A. Sweet!

He had pocket queens but my 4 aces beat his full house for a big win! I then left the table to a comment of ‘now he leaves’. I ended down on the night with -$80. So those last few hands saved my ass.

Such drama! I love it.”

A couple of things impressed me about this email: First, he didn’t get superstitious like most people and allow his previous bad luck to make him risk-averse or risk-seeking. He knew that risk is not to be avoided or sought out, it is only to be weighed. He trusted that the System worked and went all-in for that reason and that reason only. The other thing that struck me is that he was happy to end the session down $80. Poker is actually just one long session, but most people have a hard time calling it a day when they’re down. They’re tempted to keep playing even after they’re tired, and maybe even increase the stakes in an effort to get even again. The outcome shouldn’t really matter to you, just the quality of your decisions.

So is poker gambling? It can be, but doesn’t have to be. Played profitably, it’s more like an investment that can be relied on to eventually provide a positive return. Is it a game of skill? Most definitely.