So you’ve decided to invest in mutual funds and you’ve narrowed down the list to some promising candidates. You’ve got your Morningstar ratings handy and you’ve got past performance charts. What can go wrong?

Well, there’s one big problem: there’s basically no evidence that better performing fund managers aren’t just getting lucky. A study by Barras, Scaillet, and Wermers estimated that only 0.6% of over 2000 actively managed domestic equity funds actually demonstrated that skill was involved their long-term performance. Even that number wasn’t statistically significant, so the study could not rule out the possibility that absolutely no one knows how to beat the S&P. Since you’re all experts in regression to the mean now, you know exactly what to expect in the future from a fund whose past returns were entirely due to luck. You may as well pick a fund at random, or better yet, just pick the one with the lowest expense ratio, like an index fund. Actively managed funds appear to be charging for expertise that is primarily (entirely?) an illusion!

So if there’s no skill involved, why does it always look like there are so many mutual funds with great track records? It’s basically survival of the luckiest. The funds that are doing the worst are the most likely to get killed off, so when you’re only shown the survivors, you end up seeing what the victims of that stock-picking mail scam got to see: a history of hits with no visibility into the number of misses.

By the way, past performance shouldn’t cause you to hold onto stocks, either. Many people don’t want to sell stocks that have gone down since they purchased them, reasoning that they’ll eventually go back up and make a profit. A good way to find out if you actually believe the stock is still a good investment, ask yourself “if I didn’t own this stock right now, would I buy it?” If the answer is no, you should recognize that by not selling it, you are effectively doing just that. Whatever happened in the past is a sunk cost; you would either prefer to have the money or the stock.

There’s another problem that occurs when you judge investments only on their historical returns. You may find a hedge fund, for example, with huge and stable returns every year and not have any idea that this is coming…

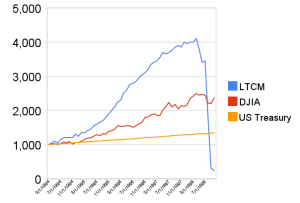

That’s what it would have looked like if you had put $1000 into the top Long-Term Capital Management hedge fund in 1994. If you think that kind of disaster looks like it couldn’t just be the result of good luck finally running out, you’re right; it has to do with financial leverage.

To demonstrate how the illusion of stability can be created through the use of leverage, consider the following simulation I created in Excel assuming a $10k initial investment and nothing better than a coin-flip’s chance at predicting the future. After 13 years, I had demonstrated a completely stable 20% return every year! You’d definitely want in on this fund, right?

| Year 1 | 20% | $ 12,000 |

| Year 2 | 20% | $ 14,400 |

| Year 3 | 20% | $ 17,280 |

| Year 4 | 20% | $ 20,736 |

| Year 5 | 20% | $ 24,883 |

| Year 6 | 20% | $ 29,860 |

| Year 7 | 20% | $ 35,832 |

| Year 8 | 20% | $ 42,998 |

| Year 9 | 20% | $ 51,598 |

| Year 10 | 20% | $ 61,917 |

| Year 11 | 20% | $ 74,301 |

| Year 12 | 20% | $ 89,161 |

| Year 13 | 20% | $ 106,993 |

You can probably guess that in year 14, it went completely broke. Behind the scenes, I was just following a Martingale strategy where I bet 20% of the money on a coin-flip and, if it didn’t work out, I’d double the size of the bet on another coin flip to make up for it. If that didn’t work out either, I still had 40% of the money left to try to get lucky and recover. If at any point I’d made the right pick and got to a 20% profit, I’d call it a day and wait until the next year to repeat the process. As long as I keep my proprietary trading strategy under lock and key (because it’s obviously so valuable), who’s going to know?

Okay, so forget trying to judge the quality of funds for yourself based on their history, how about using Morningstar ratings instead? Well, it turns out, that would also usually be worse than if you just minimized the expense ratio.

“The star rating is a grade on past performance. It’s an achievement test, not an aptitude test…We never claim that they predict the future.”

Don Phillips, President of Fund Research at Morningstar

At this point, you might be comforting yourself with the fact that you have a financial advisor who knows all of this and can dodge the pitfalls for you and recommend great investments. Unfortunately, unless you are one of the few people who uses a “fee only” advisor, there are probably some serious conflicts of interest that may have transformed your advisor into a salesman. He or she may be quietly extracting commissions of up to 8% for selling you stuff with costs hidden in places you are unlikely to discover.

The moral to the story is: forget about trying to predict the market. Get a “fee only” advisor to help you diversify broadly (into investments with low expense ratios, of course) and with an appropriate amount of risk for your situation, and don’t forget to re-balance every once in awhile. And while you’re at it, quit trying to time the market as well; the time to sell is when you need the money and the time to buy is when you have the money. Get rich slowly.